Regulation 18 draft Local Plan

(19) Chapter 4 - Climate Change

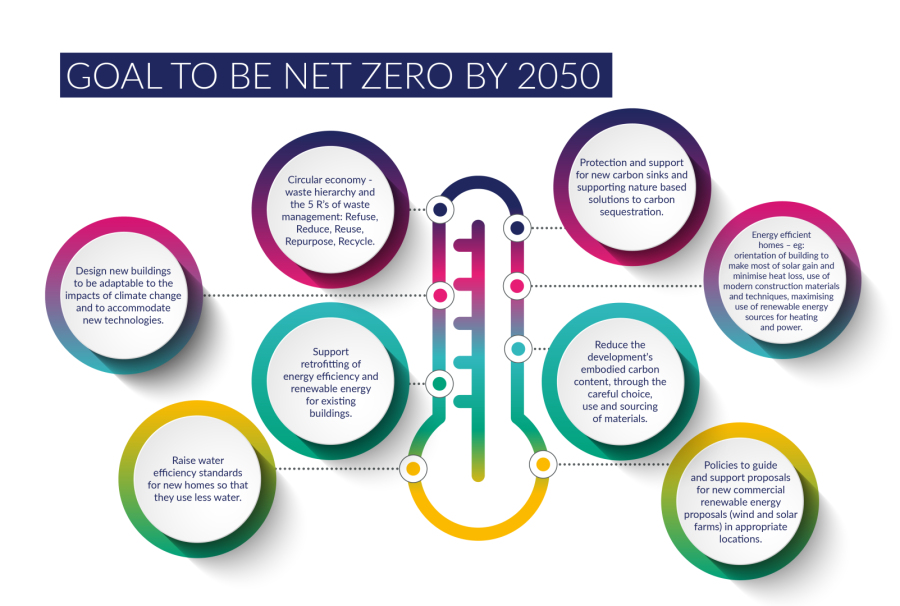

The Council recognises the need for urgent action to address climate change and has declared a Climate Crisis and Ecological Emergency. The Corporate Strategy 2022-27 recognises the objective of making Rutland a truly green county that is net zero carbon, with the challenge of reducing high levels of waste and our carbon footprint.

The Rutland Local Plan sets out both a strategic approach and relevant policies, supported by robust evidence, to address climate change, carbon reduction, as well as seeking to mitigate against the impact of climate change and supporting adaptation to such changing circumstances.

This draft plan sets out bold policies to go beyond expected national policy changes, whilst seeking to ensure that new development is viable.

Whilst this Local Plan cannot do everything (it especially has very limited influence over existing buildings, for example), it can ensure that new development is appropriate for a zero-carbon future, contributes to the transition to a net-zero carbon society, and is responsive to a changing climate.

Circular economy

A circular economy is one where materials are retained in use at their highest value for as long as possible and are then reused or recycled, leaving a minimum of residual waste. Application of circular economy principles to the built environment creates places where buildings are designed for adaptation, reconstruction, and deconstruction, extending the useful life of buildings, and allowing for the salvage of building components and materials for reuse or recycling, known as design for disassembly.

What will the policy do?

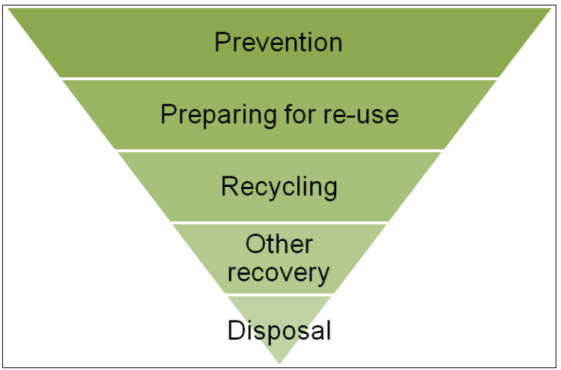

Policy CC1 aims to support development proposals that will contribute to the delivery of circular economy principles requiring proposals to demonstrate the approach to site waste management and how construction waste will be addressed following the waste hierarchy together with 5 Rs of waste management: Refuse, Reduce, Reuse, Repurpose, Recycle.

(23) Policy CC1 - Supporting a Circular Economy

The Council is fully supportive of the principles of a circular economy. Accordingly, and to complement any policies set out in the Minerals and Waste chapter of this plan, proposals will be supported, in principle, which demonstrate their compatibility with, or the furthering of, a strong circular economy in the local area (which could include cross-border activity elsewhere).

All developments (with the exception of householder applications for extensions and alterations) should set within submitted Design and Access Statements - the approach to site waste management and how construction waste will be addressed following the waste hierarchy together with 5 Rs of waste management: Refuse, Reduce, Reuse, Repurpose, Recycle.

Why is this policy needed?

Addressing climate change is one of the core land use planning principles within the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF). Section 14 of the NPPF considers the role of planning in dealing with climate change and flood risk, noting the role of planning in supporting the transition to a low carbon future in a changing climate.

Planning should help to shape places in ways that contribute to radical reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, with footnote 53 of paragraph 153 of the NPPF noting that planning policies should take a proactive approach that is be in line with the objectives and provisions of the Climate Change Act 2008. The Climate Change Act 2008 was amended in August 2019 to set a legally binding target for the UK to become net zero by 2050.

Section 182 of the Planning Act (2008) places a legal duty on local planning authorities to ensure that their development plan documents include policy to secure the contribution of development and the use of land in the mitigation of climate change.

Policies to extend the useful life of buildings as well as ensuring that, at the end of a building's life, its constituent parts are easily reused and retain maximum value, are also an important element of reducing the environmental impact of construction. Taking such an approach reduces the need to extract raw materials and the manufacture of new building components, further reducing global carbon emissions and assisting with the achievement of net zero carbon.

The Government's Resources and Waste Strategy (2018) aims to eliminate avoidable wastes of all types by 2050 in England. This includes waste from the construction sector, which is the largest user of materials in the UK and produces the biggest waste stream in terms of tonnage.

Avoiding waste and re-using waste products reduces the need for the manufacture and transport of new materials, which is an important element in achieving net zero carbon. Furthermore, efficient recycling of waste places less demands on natural and virgin resources, thereby conserving environments.

A circular economy can also be positive for the local economy, as it can create jobs in a local area to serve the circular economy, rather than support a consumption economy which relies on imports from outside the area (including international imports).

A circular economy is based on three fundamental principles: designing out waste and pollution; keeping products and materials in use; and regenerating natural systems.

The first principle requires businesses and organisations to rethink their supply chain and identify ways that they can avoid creating waste and pollution through their operations. The second principle centres around maximising the recycling, reusing, refurbishing, repairing, sharing, and leasing of resources. The third principle requires businesses and organisations to consider how they can not only protect the natural environment but also improve it. The circular economy principles can be applied at all scales- globally, locally, individual business level.

The policy approach above follows the waste hierarchy set out in the National Planning Policy for Waste (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-planning-policy-for-waste). This is shown in diagrammatic form below:

Prevention: The most effective environmental solution is often to reduce the generation of waste, including the re-use of products.

Preparing for re-use: Products that have become waste can be checked, cleaned or repaired so that they can be re-used

Recycling: Waste materials can be reprocessed into products, materials, or substances.

Other recovery: Waste can serve a useful purpose by replacing other materials that would otherwise have been used.

Disposal: The least desirable solution where none of the above options is appropriate.

Policy CC1 aims to support development proposals that will contribute to the delivery of circular economy principles. Examples of such proposals include:

- Proposals that conserve and reuse any existing buildings, structures, or materials on site to the greatest possible extent, rather than demolishing and disposing or 'downcycling' these resources;

- Proposals that will reuse unwanted materials from the local area or region;

- Proposals which have been designed to reduce material demands and enable building materials, components, and products to be disassembled and re-used at the end of their useful life;

- Proposals that incorporate sustainable waste management on-site;

- Proposals which make specific provision for the storage and collection of materials for recycling and/ or re-use; and

- Proposals for the co-location of two or more businesses/services for the purpose of sharing resources or maximising use of waste products or waste energy.

What you told us about this topic

The Issues and Options consultation highlighted a need to ensure that a positive strategy for the delivery of low carbon and renewable energy is brought forward to ensure this approach is achieved. Many respondents said that delivering net zero carbon was an important issue for them.

What alternatives have we considered?

The evidence base on climate change has considered a number of options that the Council could consider. It would be possible to not include a specific policy regarding the circular economy; however, the proposed policy sets out the Council's ambitions with respect to planning policy to address climate change.

Supporting Evidence

Which existing policies will be replaced by this policy?

No current adopted planning policies in place with respect to the Circular economy.

Design Principles for Energy Efficient Buildings

What will the policy do?

The policy establishes energy efficient design principles for new development aimed at ensuring the highest possible thermal efficiency and lowest possible expected energy use for new buildings.

The Council has adopted planning guidance on the design of new development as set out in the Rutland Design Guide SPD. In addition, the National Design Guide (January 2021) provides further guidance on design principles related to climate change and carbon reduction. A separate policy on design is set out in the Sustainable Communities chapter of this plan (Policy SC3). Policy CC2 sets out design principles to specifically address energy efficiency in new developments. This is in addition to the requirements of policy SC3 of the Sustainable Communities chapter.

(62) Policy CC2 - Design Principles for Energy Efficient Buildings

Development proposals are expected to meet the highest possible energy efficiency standards.

Planning applications should demonstrate within the Design and Access statement how the following principles have influenced the development proposed:

- orientation of buildings to optimise opportunities for solar gain and to minimise winter cold wind heat loss;

- creating buildings that are more efficient to heat and stay warm in colder conditions and stay cool in warmer conditions because of their shape and size;

- using materials and building techniques that reduce heat and energy needs, with reference to the 'U-value' (insulation value) of each building element, thermal bridging, and the airtightness of the building as a whole.

- choosing the most efficient available technologies for heating, lighting, ventilation, and (where appropriate) heat recovery from outgoing air and/or wastewater.

- net zero carbon content of heat supply (for example, this means no connection to the gas network or use of oil or bottled gas);

- maximising the generation of energy from renewable sources on-site.

Why is this policy needed?

Analysis by the Committee on Climate Change has shown that energy use minimisation in new and existing buildings is a necessary part of the achievement of the UK's legislated carbon budgets, and has defined very low heat demand targets, for new homes in particular, to be achieve from 2025 onwards

New development must be of the highest possible thermal efficiency. The expected energy use of new buildings must be as low as possible, as this has been shown to be a necessary part of the UK's achievement of its legislated net zero carbon targets. It is a false economy and unfair on future generations not to provide the highest possible thermal efficiency now. Any building that does not meet the required performance now, will require expensive and destructive retrofitting measures later at the occupier's expense. As Government itself stated in January 2021 "it is significantly cheaper and easier to install energy efficiency and low carbon heating measures when homes are built, rather than retrofitting them afterwards."( Future Homes Standard: Government Response, January 2021: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/956094/Government_response_to_Future_Homes_Standard_consultation.pdf).

Specifically, analysis produced for the Committee on Climate Change in 2019 found that to retrofit a home to the required standards (for compatibility with the UK's net zero carbon future) costs three to five times as much as it would cost to simply build to these standards in the first place (https://www.theccc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/The-costs-and-benefits-of-tighter-standards-for-new-buildings-Currie-Brown-and-AECOM.pdf). Beyond cost, this would also be highly disruptive to the occupants, which disincentivises these improvements ever occurring.

Buildings with high thermal efficiency are also more compatible with renewable and low-carbon energy systems, such as heat pumps (which typically deliver heat more slowly than conventional gas) and a renewable-heavy grid (as a home that holds onto its heat for longer can 'charge up' with heat when there's lots of renewable energy available in the grid, and doesn't need to place sudden heavy demands on the grid for heating energy at morning and evening peaks).

It is widely evidenced that extreme heat and extreme cold can have significant negative impacts on health, particularly for vulnerable people and risk of respiratory disease (https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/275839/WHO-CED-PHE-18.03-eng.pdf). Increasing energy efficiency of developments would contribute a mitigation to the negative impacts of extreme temperatures, enabling households to have healthier conditions to live.

What you told us about this topic

The Issues and Options consultation highlighted a need to ensure that a positive strategy for the delivery of low carbon and renewable energy is brought forward to ensure this approach is achieved. Many respondents said that delivering net zero carbon was an important issue for them.

What alternatives have we considered?

The evidence base on climate change has considered a number of options that the Council could consider. A key consideration for this policy has been its impact on the viability of new developments. Further work is intended to update the cost evidence to determine whether more detailed policies can be included in the next stage of the local plan.

Supporting Evidence

Which existing policies will be replaced by this policy?

No current adopted planning policies in place with respect to the Design Principles for Energy Efficient Buildings.

Climate-resilient and adaptable design

Overheating is also an area of growing concern. The Government published alongside the Future Homes Standard consultation in October 2019 research on home overheating which demonstrated that during warm years, overheating will occur in most new homes in most locations in England.

This is becoming an increasingly pressing and prevalent issue, given that climate change is already making 'hot' summers (like those of 2018 and 2022) increasingly frequent. Projections from the Met Office show that the probability of such hot summers is currently 12-25% but will reach 50-60% by the middle of the 21st Century (https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/binaries/content/assets/metofficegovuk/pdf/research/ukcp/ukcp18_headline_findings_v4_aug22.pdf).

What will the policy do?

Policy CC3 requires new development to be future proofed by being designed and constructed to be resilient to overheating and to be flexible in structure to adapt to future social, economic, environmental and technological changes.

(23) Policy CC3 - Resilient and Flexible Design

In order to ensure new development is resilient and flexible to future change proposals should consider the following in their design:

- How the design of the development minimises and prevents overheating and avoids the need for air conditioning systems;

- How the design of the development has assessed flood risk and integrated mitigation measures in line with Policy CC14;

- How the design of the development has assessed and responded to any identified need to mitigate risks related to wind exposure (including risks to occupant safety, occupant amenity, building integrity, and safety in the immediate surroundings).

- How the proposal is flexible to future social, economic, technological, and environmental requirements in order to make buildings both fit for purpose in the long term and to minimise future resource consumption in the adaptation and redevelopment of buildings in response to future needs.

Why is this policy needed?

Research has shown that overheating mitigation techniques, such as solar shading and increased ventilation, are highly effective at reducing indoor temperatures, which in turn reduces the risk of morbidity, mortality and the impact on productivity associated with sleep loss. Accordingly, as of 2022 Government has introduced a new section of Building Regulations that sets certain minimum requirements for overheating risk mitigation, in new-build homes. This new 'Part O' of Building Regulations should be read in conjunction with the above policy requirements.

Adaptations could include:

- Allow for future adaptation or extension by means of the building's internal arrangement internal height, detailed design, and construction, including the use of internal stud walls rather than solid walls to allow easier reconfiguration of internal layout;

- Provision of internal space that could successfully accommodate 'home working';

- Infrastructure that could support car free development and lifestyles;

- Having multiple well-placed entrances on larger non-residential buildings to allow for easier subdivision; and

- Is resilient to flood risk, from all forms of flooding.

What you told us about this topic

The Issues and Options consultation highlighted a need to ensure that a positive strategy for the delivery of low carbon and renewable energy is brought forward to ensure this approach is achieved. Many respondents said that delivering net zero carbon was an important issue for them.

What alternatives have we considered?

The evidence base on climate change has considered a number of options that the Council could consider. It would be possible to not include a specific policy regarding resilient and flexible design and just rely on the design policy set out in this plan and supplementary design guidance; however, the proposed policy sets out the Council's ambitions with respect to planning policy to address climate change.

Supporting Evidence

Which existing policies will be replaced by this policy?

No current adopted planning policies in place with respect to resilient and adoptable design.

Net zero carbon (operational)

What will the policy do?

Policy CC4 requires new development to be built with 'the capacity to generate its own, low – or zero - carbon, energy. For residential development, this means that as well as the high standards for space heating demands and, energy use intensity set out in policy CC2developmemnt should include the installation of renewable energy technology such as solar photovoltaics (PV) to meet the developments own energy need.

(26) Policy CC4 - Net zero carbon (operational)

All major development proposals and all residential development proposals should provide for the maximum generation of renewable electricity as practically and viably possible on-site (and preferably on-plot).

Proposals supported by an Energy Statement should cover:

- The submission of design stage estimates of energy performance; and

- Prior to any property being occupied, the submission of updated, accurate and independently verified 'as built' calculations of energy performance.

Why is this policy needed?

The Government is committed to improving the energy efficiency of new homes through the Building Regulations system, under the Future Homes Standard (FHS). The introduction of the FHS will ensure, it is proposed, that an average home will produce at least 75% lower CO2 emissions than one built to Part L 2013 standards (this is approximately equivalent to 63% reduction on today's standard, Part L 2021). This is done through improvements to the minimum standards for insulation, glazing, and efficiency of the heating system (using a heat pump as the new benchmark, instead of gas). The Government intends that homes built under the FHS will therefore be 'zero carbon ready', meaning that in the longer term, no further retrofit work for energy efficiency will be necessary to enable them to become zero-carbon homes as the electricity grid continues to decarbonise.

Working alongside the FHS, Policy CC4 sets out how new residential development in Rutland will ensure energy efficiency to the degree necessary within the UK's carbon trajectory, and also ensure that this is matched with renewable energy as the new homes come forward, so that the new growth does not add to the already huge challenge of rapidly reducing Rutland's existing emissions and reaching net zero by 2050.

What you told us about this topic

The Issues and Options consultation highlighted a need to ensure that a positive strategy for the delivery of low carbon and renewable energy is brought forward to ensure this approach is achieved. Many respondents said that delivering net zero carbon was an important issue for them.

What alternatives have we considered?

The evidence base on climate change has considered a number of options that the Council could consider. A key consideration for this policy has been its impact on the viability of new developments. Further work is intended to update the cost evidence to determine whether more detailed policies can be included in the next stage of the local plan.

Supporting Evidence

Which existing policies will be replaced by this policy?

No current adopted planning policies in place with respect to reducing energy consumption in new residential development.

Embodied Carbon

A significant proportion of a building's lifetime carbon impact is locked into its fabric and systems. This is known as Embodied Carbon means all the carbon dioxide (and other greenhouse gases) emitted in producing, transporting, constructing, using, and disposing of materials. In the case of buildings this means all the emissions from the sourcing and transportation of building materials, the construction of the building itself, its fixtures, and fittings and, finally, the deconstruction and disposal at the end of a building's lifetime. The vast majority of this embodied carbon is 'up-front,' that is, it is associated with all stages up to the completion of the building. A smaller share of the whole-life embodied carbon comes from maintenance and refurbishment across the building's lifetime, and the eventual demolition and disposal.

What will the policy do?

Policy CC5 supports measures to reduce embodied carbon through encouraging developers to demonstrate how their proposals have avoided the wastage of embodied carbon in existing buildings and avoided and reduced the creation of new embodied carbon.

(22) Policy CC5 - Embodied Carbon

All development should, where practical and viable, take opportunities to reduce the development's embodied carbon content, through the careful choice, use and sourcing of materials.

To avoid the wastage of embodied carbon in existing buildings and avoid the creation of new embodied carbon for replacement buildings, there is a presumption in favour of repairing, refurbishing, re-using, and re-purposing existing buildings over their demolition. Proposals that result in the demolition of a building (in whole or a significant part) should be accompanied by a full justification for the demolition.

Why is this policy needed?

The embodied carbon of a building typically makes up a majority share of the total carbon impact across that building's lifetime, for example the UK Green Building Council (UKGBC) has found that embodied carbon made up between 67% and 76% of buildings' total carbon emissions depending on the type of building. Clearly this must be addressed in order to fully respond to the climate emergency (especially as the share of embodied emissions that occur within the UK must be reduced in line with the UK's carbon reduction targets). Yet currently, embodied carbon is not addressed by any part of Building Regulations – there is currently no regulatory incentive for new development to reduce its embodied carbon whether through material selection, product sourcing, material-efficient design, or other means. There is therefore a need for local plan policy to respond specifically to this issue in order to fulfil the local plan's duty to mitigate climate change.

Addressing embodied carbon can provide cost-effective potential for carbon savings and cost savings over and above those traditionally targeted through operational savings. There is a significant opportunity to reduce the carbon impact of new development.

Reductions in embodied carbon are also not subject to ongoing building user behaviour in the way that operational carbon savings are. As a result, embodied carbon benefits can be more accurate, certain, and identifiable than predicted operational carbon reductions, particularly when the final occupant of the building is not known at the time.

Embodied carbon savings made during the design and construction stage are also delivered immediately. This contrasts with operational emissions savings which are delivered over time in the future. Given the long lifetime of CO2 in the atmosphere over which period its climate warming effect builds up and given the risk of reaching 'climate tipping points' or feedback loops triggering runaway climate change, the environmental value of a kg of CO2 saved today may well have a greater environmental value than a kg saved in say 10 or more 20 years' time.

Embodied carbon reduction can also contribute to other sustainability targets and priorities. For example, use of recycled content, recyclability of building materials, and reduced waste materials to landfill can all result from a focus on reducing embodied carbon and also contribute to waste reduction targets.

Similarly, benefits to the local community can accrue from cleaner fabrication processes which mitigate the impact of the development site on the local area; the use of more local sourcing and local supply chains can also support jobs; and the economy in the local area (or if not local, then at regional or national level).

What alternatives have we considered?

The evidence base on climate change has considered a number of options that the Council could consider. It would be possible to not include a specific policy regarding embodied carbon; however, the proposed policy sets out the Council's ambitions with respect to planning policy to address climate change

Supporting Evidence

Which existing policies will be replaced by this policy?

No current adopted planning policies in place with respect to reducing energy consumption in new non-residential development.

Water Efficiency

The supply and disposal of water has a significant carbon impact, as well as being a crucial issue for climate change adaptation given the increasing frequency of hotter, drier summers. Whilst the bulk (90%) of water-related carbon emissions come from the heating of water, the process of treating and pumping water to homes also has an impact (10%). Reducing water use (supply and disposal) therefore can have a significant carbon impact, even more so if that water is heated.

What will the policy do?

In recognition of the impact of domestic water usage and that Rutland is a water scarcity area, policy CC6 implements reduced water usage standards for all new homes. It also establishes principles for the sustainable management of surface water and for the provision of rainwater harvesting water butts to address issues associated with hosepipe usage.

(31) Policy CC6 - Water Efficiency and Sustainable Water Management

To minimise impact on the water environment all new dwellings should achieve the Optional Technical Housing Standard of 110 litres per day per person for water efficiency as described by Building Regulation G2. Proposals that go further than this (to, for example, 85 litres per day per person or other relevant best practice target set by the building industry such as the RIBA Climate Challenge) will be particularly encouraged.

Water Management

In addition to the wider flood and water related policy requirements (Policy CC14), all development comprising new buildings:

- with outside hard surfacing, must ensure such surfacing is permeable (unless there are technical and unavoidable reasons for not doing so in certain areas);

- with outside soft landscaping, must ensure that drought tolerant planting schemes are employed in private gardens, communal areas, and any proposed public green spaces;

- with any flat-roofed area, should be a green roof (for biodiversity, flood risk and water network benefits), unless such roof space is being utilised for photovoltaic or thermal solar panels; and

- which is residential, and which includes a garden area, must include a rain harvesting water butt(s) of minimum capacity of 200l, connected to a downpipe.

Why is this policy needed?

The 2023 climate adaptation progress report from the Parliamentary Committee on Climate Change has shown that although plans are in motion in the water supply sector to improve resilience to drought, there has been insufficient progress in reducing water demand and leakage, relative to targets. The same report shows that drought is already affecting water supplies and this risk is likely to worsen due to future climate projections for more frequent and intense dry periods combined with expected population growth.

Even small measures, such as a water butt, can make a difference – each time a 100l water butt is filled with rainwater, and used to water garden plants instead of using mains water, it saves 79g/CO2 (Source: Water UK, which estimates the carbon footprint of 1 litre of domestic water is 0.79g/CO2/l).

Building Regulations require all new residential developments to achieve a mandatory standard of 125 litres per person per day. The optional technical standard for housing allows local authorities to apply a more stringent standard of 110 litres per person per day where there is a clear local need. Rutland is identified as being within an area of serious water stress and Anglian Water Services and Severn Trent Water have provided evidence that this optional standard is required in this area. (Water Stressed Areas – 2021 Final Classification - https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/water-stressed-areas-2021-classification).

Harvesting of rainwater for garden use provides benefits both in terms of water consumption and the associated reduction in carbon impact derived from not using mains water.

What you told us about this topic

The Issues and Options consultation highlighted a need to ensure that a positive strategy for the delivery of low carbon and renewable energy is brought forward to ensure this approach is achieved. Many respondents said that delivering net zero carbon was an important issue for them.

What alternatives have we considered?

The evidence base on climate change has considered a number of options that the Council could consider. The proposed standard in the policy is the most appropriate with regard to Rutland's position as a water stressed area.

Supporting Evidence

Climate change evidence base and classification of water stressed areas

Zero Carbon Policy Options for Net Zero Carbon Developments A Climate Change Legislation

Zero Carbon Policy Options for Net Zero Carbon Developments B(i) Carbon Reduction (July 2023)

Zero Carbon Policy Options for Net Zero Carbon Developments B(ii) Risk Matrix (July 2023)

Which existing policies will be replaced by this policy?

CS 19 Promoting good design proviso d).

Existing Development – reducing energy consumption

What will the policy do?

The policy aims to assist in improving the energy efficiency of existing buildings, complementing the wider policies of this Local Plan which are primarily aimed at new buildings.

(36) Policy CC7 - Reducing Energy Consumption in Existing Buildings

For all development proposals that involve the change of use or redevelopment of a building, or an extension to an existing building, proposals are expected where possible to improve the energy efficiency of that building (including the original building, if it is being extended) through a submitted Energy Statement.

Proposals relating to an existing building that demonstrate that they will result in significant improvements to that building's operational energy efficiency and/or operational carbon emissions through on-site measures, will be expected.

The sensitive retrofitting of energy efficiency measures and the appropriate use of micro-renewables in historic buildings will be expected , including the retrofitting of listed buildings, buildings of solid wall or traditional construction and buildings within in conservation areas, whilst safeguarding the special characteristics of these heritage assets for the future.

Why is this policy needed?

Whilst there is significant new development planned for Rutland, the vast majority of buildings that will be occupied over the coming decades will be those built in earlier times when energy and performance standards were much lower than at present.

An Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) provides details of the energy performance of a property and is required for properties when constructed, sold, or let.

The Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards (MEES) Regulations require all applicable properties to achieve an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) rating of E or better. Separately, the Clean Growth Strategy (2017) has set a target for as many buildings as possible to achieve an EPC of C by 2030/35 and commits to keep energy efficiency standards under review.

The Council intends to bring forward supplementary guidance regarding a Carbon Zero Toolkit, already promoted by other local planning authorities. It encourages the use of the Carbon Zero Toolkit that the Council shall promote for the time being alongside the PAS 2035:2019 Retrofitting Dwellings for Improved Energy Efficiency: Specifications and Guidance. This offers an end-to-end framework for the application of energy retrofit measures to existing buildings in the UK and provides best practices for their implementation. It is a key document in a framework of new and existing standards on how to conduct effective energy retrofits of existing buildings. It covers how to assess dwellings for retrofit, identify improvement options, design, and specify Energy Efficiency Measures (EEM) and monitor retrofit projects. A related standard, BS40101, expresses best practice in evaluating the performance of buildings (including energy as well as other factors such as air quality) and can be very helpful to identify building energy performance issues before targeting these through energy retrofit interventions.

What you told us about this topic

The Issues and Options consultation highlighted a need to ensure that a positive strategy for the delivery of low carbon and renewable energy is brought forward to ensure this approach is achieved. Many respondents said that delivering net zero carbon was an important issue for them.

What alternatives have we considered?

A key consideration for this policy has been its impact on the viability of new developments. Further work is intended to update the cost evidence to determine whether more detailed policies can be included in the next stage of the local plan

.Supporting Evidence

Which existing policies will be replaced by this policy?

CS 19 Promoting good design proviso c) and SP15 Design and Amenity

Renewable Energy Generation

The generation and use of renewable energy reduces demand for fossil fuels, thus reducing harmful greenhouse gas emissions. Renewable energy technologies include:

- Photovoltaic solar panels - for electricity generation

- Thermal solar panels- for heating

- Wind turbines - for electricity generation

- Ground source heat pumps – for heating

- Air source heat pumps – for heating

The use of renewable energy not only reduces carbon emissions – and so help address climate change - but it also has other benefits such as:

- it is sustainable - renewable energy will not run out, unlike fossil fuels which are finite;

- the renewable energy sector creates jobs in the short and long term, for example, project planning, installation, operation and maintenance;

- onshore wind offers the most cost-effective choice for electricity in the UK and these cost savings can be passed onto the consumer;

- onshore wind technology is getting more efficient whilst maintaining the same footprint, and land between wind turbines can be used for other productive purposes, such as food production

- generating energy locally for local consumption reduces the local exposure to volatile prices or supply interruptions caused by disruptions elsewhere, enhancing the degree of control Rutland has over its own decisions and ability to thrive (energy sovereignty).

What will the policy do?

Policy CC8 seeks to maximise appropriately located renewable energy generated in Rutland by establishing the areas of the County where different types of large-scale renewable energy proposals may be acceptable and setting out the criteria against which proposals will be assessed. The policy also sets out provisions for the decommissioning of renewable energy sites.

(89) Policy CC8 - Renewable Energy

The Council is committed to supporting the transition to a net zero carbon future and will seek to maximise appropriately located renewable energy generated in Rutland.

Proposals for renewable energy schemes, including ancillary development, will be supported where the direct, indirect, individual, and cumulative impacts on the following considerations are, or will be made, acceptable. To determine whether it is acceptable, the following tests will have to be met:

- The impacts are acceptable having considered the scale, siting and design, and the consequent impacts on landscape character; visual amenity; biodiversity; geodiversity; flood risk; townscape; heritage assets, their settings, and the historic landscape; and highway safety; and

- The impacts are acceptable on aviation and defence navigation system/communications; and

- The impacts are acceptable on the amenity of sensitive neighbouring uses (including local residents) by virtue of matters such as noise, dust, odour, shadow flicker, air quality and traffic.

Compliance with part (a) above will be via applicable policies elsewhere in a development plan document for the area (i.e., this Local Plan or a Neighbourhood Plan, if one exists); and any further guidance set out in a Supplementary Planning Document.

Compliance with part (b) above will require, for relevant proposals, the submission by the applicant of robust evidence of the potential impact on any aviation defence navigation system/communication, including documented areas of agreement or disagreement reached with appropriate bodies and organisations responsible for such infrastructure.

Compliance with part (c) above will require, for relevant proposals, the primary obligation would be for the Applicant to present a robust assessment that would be considered in the context of all other submissions made , and the mitigation measures proposed to minimise any identified harm.

For meeting the above criteria (a)-(c), the County Council may commission its own independent assessment of the proposals, to ensure it is satisfied what the degree of harm may be and whether reasonable mitigation opportunities are being taken.

In areas that have been designated for their national importance, as identified in the National Planning Policy Framework, renewable energy infrastructure will only be permitted where it can be demonstrated that it would be appropriate in scale, located in areas that do not contribute positively to the objectives of the designation, is sympathetically designed and includes any necessary mitigation measures.

Community renewable energy proposals

Weight in favour will be afforded to renewable energy proposals where community ownership or significant benefits to local communities are demonstrated.

Additional considerations for solar based energy proposals

Proposals for the installation of solar thermal or photovoltaics panels and associated infrastructure on an existing building will be under a presumption in favour of permission unless there is clear and demonstrable significant harm arising.

Proposals for ground based solar thermal or photovoltaics and associated infrastructure, including commercial large-scale proposals, will be supported where they are within an area identified as a "ground mounted solar PV opportunity area" as identified on the Policies Map and address all matters in (a) – (c) above, as well as the additional requirements of national planning policy, unless:

- there is clear and demonstrable significant harm arising; or

- the proposal is (following a site-specific soil assessment) to take place on Best and Most Versatile (BMV) agricultural land, the proposal is part of a wider scheme to protect or enhance a carbon sink of such land or unless the agricultural production can continue during the operation of the energy generation or can recommence after the end of life of the energy generation equipment without significant impact on the quality of that agricultural land ; or

- the land is allocated for another purpose in this Local Plan or other statutory based document (such as a Nature Recovery Strategy or a Local Transport Plan), and the proposal is not compatible with such other allocation.

Additional matters for wind-based energy proposals

Proposals for a small to medium single wind turbine, which is defined as a turbine up to a maximum of 40m from ground to tip of blade, are, in principle, supported throughout Rutland. Such proposals will be tested against criteria (i)-(iii) and the additional requirements of national planning policy.

Proposals for medium (over 40m from ground to tip of blade) to large scale wind turbines (including groups of turbines) will, in principle, be supported only where they are within an area identified as a "broad area suitable for Larger Scale Wind Energy Turbines" as identified on the Policies Map and address all matters in (a) – (c) above, as well as the additional requirements of national planning policy.

Medium to large scale wind turbines should not be within 500m of any settlement or individual residential property. Any proposal for a medium to large scale wind turbine located between 500-2000m of residential property will need clear evidence of no significant harm arising. This would include assessment of:

- noise

- flicker

- overbearing nature of the turbines (established by visual effects from within commonly used habitable rooms)

- any other amenity which is presently enjoyed by the occupier

Decommissioning renewable energy infrastructure

Where permitted, proposals will be subject to a condition that will require the submission of an End-of-Life Removal Scheme within six months of the facility becoming non-operational, and the implementation of such a scheme within one year of the scheme being approved. Such a scheme should demonstrate how the biodiversity net gain that has arisen on the site will be protected or enhanced further, and how the materials to be removed would, to a practical degree, be re-used or recycled in line with Policy CC1.

Why is this policy needed?

In June 2015 Government issued a Written Statement on wind energy development (https://www.parliament.uk/globalassets/documents/commons-vote-office/June-2015/18-June/1-DCLG-Planning.pdf) stating that, when determining planning applications for wind energy development involving one or more wind turbines, local planning authorities should only grant planning permission if:

- the development site is in an area identified as suitable for wind energy development in a local or neighbourhood plan; and

- following consultation, it can be demonstrated that the planning impacts identified by affected local communities have been fully addressed and therefore the proposal has their backing.

This has recently been updated in a Written Statement issued on 5th September 2023 (https://questions-statements.parliament.uk/written-statements/detail/2023-09-05/hcws1005). These are currently reflected in the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) up to the 2021 edition of the NPPF. At the time of drafting this local plan policy wording, the Government recently proposed to update the NPPF in 2023 to specify instead that the community's identified impacts must be "satisfactorily" or "appropriately" addressed (rather than 'fully') and that wind energy development should have "community support" rather than "their backing". Although subtle, these changes would recognise that there can be diversity of opinion within the community on the acceptability of wind energy development, and therefore that there may be situations where wind energy development can be deemed permissible without it being practical to 'fully' address every concern that each community member may hold.

The proposed NPPF changes also include that wind energy development could also be granted through Local Development Orders, Neighbourhood Development Orders or Community Right to Build Orders. Rutland Council will monitor the outcome of these proposed NPPF changes and will make any necessary or appropriate adjustments to the emerging local plan policies to reflect these changes should they be confirmed by Government before the Local Plan goes to examination.

This Local Plan identifies potentially suitable areas for wind turbine development. Not identifying potentially suitable areas for wind turbine development would potentially make the goal of net zero carbon, whether by 2050 (UK legal requirement) or earlier (and the UK's legislated carbon budgets before 2050) harder to achieve, and result in greater pressure to adopt more revolutionary measures elsewhere. In principle, therefore, this Local Plan supports and helps facilitate the delivery of wind turbines. in addition to other forms of renewable energy generation, storage, and distribution.

Policy CC8 differentiates between small to medium scale turbines and medium to large turbines.

This Local Plan establishes that the whole of the Rutland area is potentially suitable for small to medium wind turbine development, while only the limited areas as defined on the Policies Map are potentially suitable for the development of medium to large scale turbines.

It is important to stress that the areas on Map and the Policies Map are only 'potentially suitable' for medium-large scale wind turbines: being within these locations does not mean that an application for a wind turbine or turbines would automatically be approved. It is not possible to map qualitative considerations easily and comprehensively, so such matters are considered at the point of application: all applications for wind turbines will be assessed against the detailed policy criteria set out in Policy CC8, and all other relevant policies in this Local Plan, as well as policies in any relevant Neighbourhood Plan.

Sites that are potentially suitable for solar renewable energy are also identified on the Policies Map.

In addition, applicants will also have to demonstrate that any planning impacts identified by affected local communities have been appropriately addressed, in order to satisfy national policy (See NPPF (2023) paragraph 158 and footnote 54). Whether a proposal has the backing or support of the local community is a judgement the Council will make on a case-by-case basis.

Beyond the specific issue of wind to consider renewable energy generation as a whole, it is clear that further action (beyond existing national policy) is needed based on evidence from the Committee on Climate Change Progress Report (2023) which flags that although some progress has been made recently on reducing the carbon intensity of electricity, "The Government is still lacking a credible overall strategy for delivering its objective of decarbonising the sector by 2035" and "credible plans are in place for [only] around 30% of the emissions reduction required [in this sector] by the Sixth Carbon Budget" .

The CCC 2023 report also notes that although renewable energy generation capacity grew in the past year, this is still behind the levels needed to hit government targets. The growth that occurred was primarily through offshore wind, while "both onshore wind and solar deployment are progressing more slowly … in part due to barriers in the planning system."

What you told us about this topic

The Issues and Options consultation highlighted a need to ensure that a positive strategy for the delivery of low carbon and renewable energy is brought forward to ensure this approach is achieved. Many respondents said that delivering net zero carbon was an important issue for them.

What alternatives have we considered?

The proposed approach is in line with national policy guidance.

Supporting Evidence

A key consideration for this policy has been its impact on the viability of new developments. Further work is intended to update the cost evidence to determine whether more detailed policies can be included in the next stage of the local plan.

Which existing policies will be replaced by this policy?

CS20 – Energy efficiency and low carbon generation

SP18 Wind turbines and low carbon energy developments

Wind Turbines SPD.

There are no current adopted planning policies in place with respect to other forms of renewable energy.

Protecting Renewable Energy Infrastructure

What will the policy do?

Policy CC9 safeguards existing renewable energy schemes and installations, to ensure that their benefits to the environment and users continue into the future.

(5) Policy CC9 - Protecting Renewable Energy Infrastructure

Development should not significantly harm:

- the technical performance of any existing or approved renewable energy generation facility;

- the potential for optimisation of strategic renewable energy installations; and

- the availability of the resource, where the operation is dependent on uninterrupted flow of energy to the installation.

Why is this policy needed?

In order to support the transition to a zero carbon Rutland, there is a need to move away from fossil fuels towards low carbon alternatives and this transition needs to take place with increasing momentum in order to stay within identified carbon saving targets.

The evidence of need for greater action on renewable energy generation from the Committee on Climate Change 2023 progress report, previously cited under the rationale for Policy CC8 (Renewable Energy), also applies to this policy CC9 as both relate to the need for an acceleration in the total amount of renewable energy generation in order to hit nationally legislated carbon budgets and national commitments around decarbonisation of the energy sector.

What you told us about this topic

The Issues and Options consultation highlighted a need to ensure that a positive strategy for the delivery of low carbon and renewable energy is brought forward to ensure this approach is achieved. Many respondents said that delivering net zero carbon was an important issue for them.

What alternatives have we considered?

The evidence base on climate change has considered a number of options that the Council could consider. It would be possible to not include a specific policy regarding protecting renewable energy infrastructure; however, the proposed policy sets out the Council's ambitions with respect to planning policy to address climate change.

Which existing policies will be replaced by this policy?

There are no current adopted planning policies in place with respect to renewable energy infrastructure.

Energy Infrastructure

What will the policy do?

The Council is committed to supporting the transition to net zero carbon future and, in doing so, recognises and supports, in principle, the need for significant investment in new and upgraded energy infrastructure.

(8) Policy CC10 - Wider Energy Infrastructure

Where planning permission is needed, support will be given to proposals that are necessary for, or form part of, the transition to a net zero carbon sub-region, which could include: energy storage facilities (such as battery storage or thermal storage); and upgraded or new electricity facilities (such as transmission facilities, sub-stations or other electricity infrastructure).

However, any such proposals should take all reasonable opportunities to mitigate any harm arising from such development and take care not only to select appropriate locations for such facilities, but also to design solutions which minimise harm arising.

Why is this policy needed?

In order to support the transition to a zero carbon Rutland, there is a need to move away from fossil fuels towards low carbon alternatives and this transition needs to take place with increasing momentum in order to stay within identified carbon saving targets.

There may also be a need arising in future to consider future forms of potentially low-carbon energy, such as hydrogen (noting that hydrogen's role in the UK's net zero carbon transition is anticipated to be mainly in heavy industry, transport, and storage of excess renewable electricity, rather than becoming a direct replacement for natural gas in homes and other heated buildings).

The key implication of the move towards low carbon energy will be the increasing demand for electricity. Meanwhile, the latest calculations of the UK's optimal pathway to net zero carbon, including the necessary transition of buildings and transport to electricity (instead of gas and petrol/diesel), should result in an electricity demand increase from 2020 levels of 53% by 2035 and doubling by 2050.

In addition to the increase in demand, the electricity grid will also need to become more able to respond to greater peaks and troughs in energy generation as the generation mix becomes more renewable-heavy, as renewable energy generation such as wind and solar can be more intermittent (compared to conventional fossil fuels which can be increased or decreased in rapid response to the demands being placed on the grid). This means our future grid, to be fit for net zero carbon future, needs to become able to store energy for later use, smartly direct energy from where it is generated to where it is needed, and be able to maintain frequency throughout rapid fluctuations in the generation and demand. The Royal Town Planning Institute states that in addition to bringing forward renewable energy generation, the planning system will also need to "play a key role in aiding a transmission strategy by helping deliver the next generation of energy connections, storage and smart grid infrastructure."

As a result, the infrastructure around energy will need to adapt and change to accommodate the increased need for the management and storage of electricity. Consideration of existing and new electricity sub-stations, storage and energy strategies for large developments will be required to help support the future energy infrastructure needs for Rutland.

What you told us about this topic

The Issues and Options consultation highlighted a need to ensure that a positive strategy for the delivery of low carbon and renewable energy is brought forward to ensure this approach is achieved. Many respondents said that delivering net zero carbon was an important issue for them.

What alternatives have we considered?

The evidence base on climate change has considered a number of options that the Council could consider. It would be possible not to include a specific policy regarding wider energy infrastructure; however, the proposed policy sets out the Council's ambitions with respect to planning policy to address climate change.

Which existing policies will be replaced by this policy?

There are no current adopted planning policies in place with respect to renewable energy infrastructure.

Carbon Sinks and Sequestration

Carbon sequestration is the capture, removal, and long-term storage of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and is recognised as a key component in mitigating (or if at sufficient scale, potentially reversing) climate change. Carbon dioxide is naturally captured from the atmosphere through biological, chemical, and physical processes and is stored in vegetation, soils, and oceans. These are often referred to as carbon sinks. On land (and wetland), the main process by which this occurs is through the conversion of carbon dioxide into plant tissue through plants' growth processes, where it can be locked up for the plant's lifetime or longer if the plant tissue carbon is eventually trapped in soils or under water. The way in which we manage these carbon sinks can have a significant impact on carbon sequestration.

These processes can be accelerated or decelerated through changes in land use. For example, land currently used for non-crop purposes (such as trees or grasslands) which is lost to other uses (such as development or intensive agriculture) can reduce or even stop carbon sequestration from happening on that land. Drainage of wetlands (especially peat) can cause large releases of carbon as the formerly submerged soil is exposed to air. Vice versa, land which has no material carbon sequestration currently occurring can be converted, via alternative land use, to one which commences carbon sequestration. Overall, we need to protect land which has a role of positive carbon sequestration, and where possible create additional land fulfilling that function. To indicate the scale of action needed, the 2023 progress report on the UK's climate mitigation efforts shows that to hit the UK's committed carbon targets, the current tree-planting rate is too low (needing to double by 2025) and so does the rate of peatland restoration (currently less than one-fifth of the rate it should be). Afforestation in particular is expected to play a key role in the UK's carbon targets, needing to increase the UK's forested area from 13% in 2020, to reach 15% in 2035 and 18% in 2050.

What will the policy do?

Policy CC11 seeks to protect existing carbon sinks from development and promotes opportunities to enhance the function of existing carbon sinks

Policy CC12 covers carbon sequestration, providing support to proposal where the net outcome is demonstrated to be a significant gain in nature-based carbon sequestration as a consequence of the proposal.

(19) Policy CC11 - Carbon Sinks

Existing carbon sinks should be protected, and where opportunities exist, they should be enhanced in order to continue to function as a carbon sink. Where development is proposed on land containing peat soils or other identified carbon sinks, including woodland, trees, hedges, orchards, and scrub; open habitats and farmland and rivers, lakes, reservoirs and wetland habitats, the applicant must submit a proportionate evaluation of the impact of the proposal on any form of identified carbon sink as relevant. In all cases an appropriate management plan must be submitted.

There will be a presumption in favour of preservation of carbon sinks in-situ. Proposals that will result in unavoidable harm to, or loss of identified carbon sinks will only be permitted if it is demonstrated that:

- the site is allocated for development; or

- there is not a less harmful viable option for development of that site.

In any such case, the harm caused must be shown to have been reduced to the minimum possible and appropriate, satisfactory provision will be made for the evaluation, recording and interpretation of the peat soils or other form of carbon sink before commencement of development. Proposals to help strengthen existing, or create new, carbon sinks will be supported.

(9) Policy CC12 - Carbon Sequestration

The demonstration of meaningful carbon sequestration through nature-based solutions within a proposal will be a material consideration in the decision-making process. Material weight in favour of a proposal will be given where the net outcome is demonstrated to be a significant gain in nature-based carbon sequestration as a consequence of the proposal. Where a proposal will cause harm to an existing nature-based carbon sequestration process, weight against such a proposal will be given as a consequence of the harm, with the degree of weight dependent on the scale of net loss.

Why these policies are needed

Land plays a significant role in climate objectives, acting as both a source of greenhouse gas emissions and a carbon sink in the achievement of local and national carbon reduction commitments. Habitats such as woodlands and grasslands have a role to play in this regard. Alongside many other negative impacts, loss and degradation of natural habitats results in the direct loss of carbon stored within them.

Land based carbon sequestration, alongside technological means for removing carbon from the atmosphere, will have a role to play. While the role of planning in supporting the development of land for carbon sequestration is limited, planning policies already exist to protect nature sites, which almost without exception will function as a carbon sink, and further policies exist to require new development to provide new open space and deliver biodiversity net gain. However, in the absence of Policy CC12 there would be no requirement for the carbon sink function of land to be specifically considered at all in development decisions. Promotion of nature-based solutions, where natural systems are protected, restored, and managed can assist with the protection of carbon sinks while at the same time providing benefits for biodiversity and health and wellbeing. See also policies EN1- EN11 in the Chapter 9 Environment

What you told us about this topic

The Issues and Options consultation highlighted a need to ensure that a positive strategy for the delivery of low carbon and renewable energy is brought forward to ensure this approach is achieved. Many respondents said that delivering net zero carbon was an important issue for them.

What alternatives have we considered?

The evidence base on climate change has considered a number of options that the Council could consider. It would be possible not to include a specific policy regarding carbon sinks and carbon sequestration; however, the proposed policy sets out the Council's ambitions with respect to planning policy to address climate change.

Which existing policies will be replaced by these policies?

There are no current adopted planning policies in place with respect to carbon sinks and carbon sequestration.

Facilitating a Transition to Net-zero Carbon Lifestyles

Rutland's emissions come from a variety of sectors and activities. The Local Plan can influence many of these to a varying extent, but not to the full extent that would ensure a transition to net zero carbon across the whole plan area. National policy, sectoral practices, technological advance, and individual behaviours will also shape the carbon outcomes.

What will the policy do?

Nationally prescribed building regulations establish requirements for electric vehicle charging points for specific development proposals, Policy CC13 establishes local requirement for the location and implementation of the national requirements relating to EV charging. It also sets out requirement for secure and covered bicycle parking suitable for e-bikes which are large and heavy to bring into premises.

(24) Policy CC13 - Sustainable Travel

All applications that include provision of parking spaces will be required to meet the requirements set out in the Building Regulations Part S (or successor). The location of charging points in development proposals should be appropriately located to allow for easy and convenient access from the charge point to the parking space/s, and be designed and located in a way which:

- minimises the intrusion of the charge point on the wider use and access of the land;

- minimises the risk of vehicle collision with the charge point; and

- has ease of access for maintenance and replacement of electric vehicle charging infrastructure.

Proposals that include electric vehicle parking provision that exceeds or improves on the requirements set by Building Regulations will be supported. Examples of how these might be exceeded include:

- proposing a higher ratio of charging points to parking spaces than the ratio required by Building Regulations, especially in non-residential development

- proposing active charging points in types of parking that are currently not required by Building Regulations to have a charge point

- proposing to provide or fund electric charging points for existing public parking expected to be used by the development's occupants or visitors

- proposing chargers that have vehicle-to-grid capacity

- proposing some points that provide a faster charge than the standard set by Building Regulations, especially in any parking spaces expected to be used for short visits such as retail, medical, leisure, or similar.

In addition, appropriate provision should be made for secure and covered bicycle parking suitable for e-bikes which are large and heavy to bring into premises.

Why is this policy needed?

Transport is the largest source of CO2 emissions in the UK. This is mostly due to road transport, where small increases in fuel efficiency have been cancelled out by an increase in mileage. Transport emissions have remained fairly similar in recent years, in contrast to other sectors where emissions have decreased. A switch to electric vehicles is underway but has been slow. The national ban on new diesel and petrol cars from 2030 will help, but existing cars will remain in use long after that. Nevertheless, it is beyond doubt that we are at the start of the transition away from fossil fuel combustion engines to electric vehicles, a process which may have almost come to its conclusion by the end date of this Local Plan.

With such monumental change on the horizon, it is imperative that the built environment be ready. In December 2021, the Building Regulations were updated with a new Part S being added which addresses Infrastructure for charging electric vehicles. These regulations came into effect in June 2022 and require the provision of charging points in both residential and non-residential developments, with specific levels of requirements set out for uses, not for every parking space to be provided with a charging point.

As a result of these new Building Regulations, Policy CC13 does not seek the basic provision of electric vehicle charging points, but, given that we will all be expected to drive electric vehicles in the not-too-distant future, it seeks to ensure that the location of electric vehicle charging points to be well situated to ensure that they will be readily accessible to future users.

It also seeks to acknowledge the benefits brought by any development proposals that include an enhanced electric vehicle charging provision (beyond the minimum standard required by Building Regulations Part S) to strategically facilitate wider uptake of electric vehicles. For example, Part S only requires chargers of a minimum 7kW; although this meets the industry definition of 'fast' charging (7 – 23kW) this typically would take 3-4 hours to charge a small electric car. As an improvement on this, 'rapid' chargers (43kW supply or more) enable a meaningful amount of battery charge to be achieved at short-stay parking, forming a potentially vital steppingstone for long-distance electric vehicle trips and a lifeline for drivers who do not have guaranteed access to charging at home or at work.

Vehicle-to-grid capacity is also noted as an optional enhancement in charger provision because this function is thought to have potential to support the transition to a smarter and more flexible electrical grid needed by the UK's future renewable-heavy energy system. This function could enable electric vehicles to play an 'energy storage' role in the grid, with potential additional benefits for the EV owner in the ability to sell energy back to the grid at times of peak grid demand (having previously charged the car at a time of low grid demand and excess renewable generation).

What you told us about this topic

The Issues and Options consultation highlighted a need to ensure that a positive strategy for the delivery of low carbon and renewable energy is brought forward to ensure this approach is achieved. Many respondents said that delivering net zero carbon was an important issue for them.

What alternatives have we considered?

The evidence base on climate change has considered a number of options that the Council could consider. It would be possible not to include a policy regarding specific climate change issues related to sustainable policy and just rely on other policies set out in this plan; however, the proposed policy sets out the Council's ambitions with respect to planning policy to address climate change.

Which existing policies will be replaced by this policy?

There are no current adopted planning policies in place with respect to facilitating a transition to net-zero lifestyle.

Adapting to Climate Change

This section acknowledges that climate change is happening and, even if we meet our legal obligations set by the Paris Agreement and the Climate Change Act 2008, there will be consequences that society will have to prepare for and learn to adapt to. It is important that new development enables society to respond to that change and adapt our built environment to accommodate those changes.

What will the policy do?

Policy CC14 seeks to ensure that development does not place itself or others at increased risk of flooding. making sure that new development takes full account of flood risk, both current risk and future forecast risk, applying both the sequential test for flood risk and the surface water hierarchy for addressing issues of surface water management.

(27) Policy CC14 - Flood Risk

To reduce the risk of flooding, all major development proposals will be considered against the NPPF, including application of the sequential test and, if necessary, the exception test.

Where appropriate development proposals should demonstrate:

- that the development does not place itself or other land or buildings at increased risk of flooding;

- that the development will be resilient to flood risk from all forms of flooding such that in the event of a flood the development could be quickly brought back into use without significant refurbishment;

- that the development does not affect the integrity of existing flood defences and any necessary flood mitigation measures have been agreed with the relevant bodies, where adoption, ongoing maintenance and management have been considered and any necessary agreements are in place;

- how proposals have taken a positive approach to reducing overall flood risk and have considered the potential to contribute towards solutions for the wider area; and

- that they have incorporated Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS)/ Integrated Water Management into the proposals unless it is shown to be inappropriate for that specific proposal.

- that they have followed the surface water hierarchy for all proposals:

- surface water runoff is collected for use;

- discharge into the ground via infiltration;

- discharge to a watercourse or other surface water body;

- discharge to a surface water sewer, highway drain or other drainage system,

- discharge to a combined sewer;

- that surface water connections are acceptable to the relevant agency;

- that development contributes positively to the water environment and its ecology where possible and does not adversely affect surface and ground water quality in line with the requirements of the Water Framework Directive;

In order to allow access for the maintenance of watercourses, development proposals that include or abut a watercourse should ensure no building, structure or immovable landscaping feature is included that will impede access within 8m of a watercourse. Conditions may be included where relevant to ensure this access is maintained in perpetuity and may seek to ensure responsibility for maintenance of the watercourse including land ownership details up to and of the watercourse is clear and included in maintenance arrangements for future occupants.

Why is this policy needed?

Rutland's rivers and water resources are a valuable asset, supporting wildlife, recreation, and tourism, as well as providing water for businesses, households, and agriculture. Water resources require careful management to conserve their quality and value and to address drainage and flooding issues.

Flood Risk

In accordance with the NPPF and supporting technical guidance, Policy CC14 seeks to ensure that development does not place itself or others at increased risk of flooding. All development will be required to demonstrate that regard has been given to existing and future flood patterns from all flooding sources and that the need for effective protection and flood risk management measures, where appropriate, have been considered as early on in the development process as possible.

A sequential risk-based approach to the location of development, known as a 'sequential test,' will be applied to steer new development to areas with the lowest probability of flooding. If, following the application of the sequential test, it is not possible, consistent with wider sustainability objectives, for development to be located in areas with a lower probability of flooding, the exception test may be applied. The exception test, in line with NPPF, requires development to show that it will provide wider sustainability benefits to the community that outweigh flood risk, that it would be safe for its lifetime taking account of the vulnerability of its users, without increasing risk elsewhere and, where possible, will reduce flood risk overall.

Rutland contains areas of low-lying land for which a number of organisations are responsible for managing flood risk and drainage, including the Environment Agency (EA), Rutland County Council as Lead Local Flood Authority (LLFA), Anglian Water and Severn Trent Water Companies, the Canal and River Trust, and a number of Internal Drainage Boards (IDBs).

Many of Rutland's settlements were originally established adjacent to rivers or other water bodies. Over time these same settlements have grown and now represent, in terms of wider sustainability criteria, the most sustainable locations for future development. A careful balance therefore needs to be struck between further growth in these areas to ensure their communities continue to thrive and the risk of flooding.

With the increased likelihood of more intense rainfall combined with further development in Rutland, there will be an increase in the incidence of surface water runoff, placing greater pressure on existing drainage infrastructure. The discharge of surface water to combined sewer systems should be on an exceptional basis only. This will ensure that capacity constraints of existing systems are not put under severe pressure by placing unnecessary demands on existing sewage works and sewage systems which in turn could compromise the requirements of the Water Framework Directive. The discharge of surface water to combined sewer systems can also contribute to surface water flooding elsewhere.

Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS) are used to replicate, as closely as possible, the natural drainage from a site before development takes place without transferring pollution to groundwater. Developers should ensure that good SuDS principles consistent with national standards such as The SuDS Manual (C753 – CIRIA) are considered and incorporated into schemes as early in the development process as possible. A multi-functional approach to SuDS is encouraged that should take every opportunity to incorporate features that enhance and maintain biodiversity as part of a coherent green and blue infrastructure approach. The use of Integrated Water Management is encouraged for larger scale developments.

Protecting the Water Environment

The Council works closely with water companies, the Environment Agency, and other relevant bodies to ensure that infrastructure improvements to manage increased wastewater and sewage effluent produced by new development are delivered in a timely manner, and to ensure that, as required by the Water Framework Directive, there is no deterioration to water quality and the environment.

All relevant development proposals, where appropriate, should be discussed with the Local Planning Authority in liaison with the EA, Water Services Provider, IDBs and the LLFA at the earliest opportunity, preferably at pre-application stage. This should ensure flood risk and drainage solutions, particularly where required on site, can be factored into the development process as early as possible.

What you told us about this topic

The Issues and Options consultation highlighted a need to ensure that a positive strategy for the delivery of low carbon and renewable energy is brought forward to ensure this approach is achieved. Many respondents said that delivering net zero carbon was an important issue for them.

What alternatives have we considered?

The evidence base on strategic flood risk assessment has considered a number of options that the Council could consider.

Which existing policies will be replaced by this policy?

Flood risk and surface water management are covered within policy CS19 – Promoting good design and SP15 Design and Amenity